Strategies and tools to know societies’ concerns and address them in our health messaging, especially in the current COVID-19 emergency

Adapting information to the audience is crucial to meet their needs and values. These are unique and influenced by multiple factors such as context and background, age, gender, education level and health literacy. The current COVID-19 situation demands rapid action, and while careful tailoring may appear to be more time consuming than a standard message, any effort to ensure that the information is well targeted will increase its’ effectiveness and impact. This is vital in the context of a health emergency.

To promote a tailored communication process, this post presents our experience of one potential co-design approach called “Design Thinking”. i-CONSENT consortium has used this methodology to adapt health information to the audience to better tailor communications to their specific needs and conditions.

What is Design Thinking?

Design Thinking is a human-centred process for creative problem solving. It encourages taking a ‘designerly’ mindset to meet the needs of end users which can lead to better products, services, and processes. It is a rapid and iterative process in which solutions are quickly prototyped, tested, and improved until it becomes a final product.

Design Thinking workshops are one of many ways of approaching this process. This is the approach that we used in the iCONSENT project. In addition to face-to-face, Design Thinking workshops can be done virtually (through teleconference software, for example). This makes it a more appropriate method in this time of social distancing. To choose the best method for you and become an effective facilitator, we recommend that you follow Design Thinking courses that are led by experts in the field such as IDEO.

What did the iCONSENT Design Thinking approach look like?

We know that to practically develop a relevant solution, it is really important to understand the perspectives and gain the input of a variety of stakeholders. To communicate with the general public, we therefore co-designed solutions with them, in our case it was doctors, social scientists, and researchers.

To develop a solution that meets the diverse needs of the general public, we found that Design Thinking helped to work with a range of people. i-CONSENT particularly focused on adults and children. Lenses that could be interesting to consider for a problem such as tailoring communication for COVID-19 could be, for example, disease status (vulnerable groups vs. the healthy), people in different socioeconomic groups, from different cultures, and of different genders.

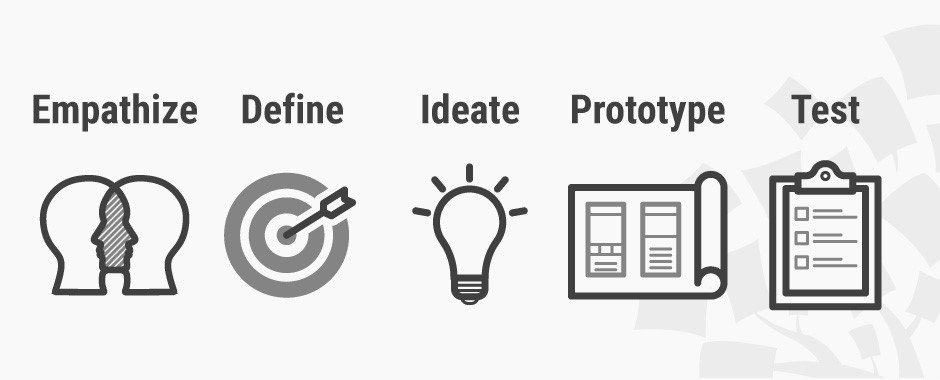

The Design Thinking approach is based around five main pillars – empathise, define, ideate, prototype, and test. i-CONSENT decided to conduct workshops but there are different ways of working through these pillars. Here some basics on i-CONSENT’s approach:

1. Empathise: The idea for this stage is to “put yourself in the shoes” of the user. In the case of COVID-19, to understand what the publics’ primary needs are it could be useful to better understand the main concerns, fears, and priorities, for example. In our project we did this through role play – imagining scenarios related to receiving experimental vaccines, combined with simple Design Thinking methodologies such as ‘empathy mapping’. It is important to note that technology provides new opportunities to help gain insights from society which could be particularly valuable in the context of this pandemic. In addition to the methods noted above, some other potential ways to build empathy at an early stage could be:

- Exploring the available literature on your target population through literature review. This can provide useful insights about audience needs and preferences previously identified.

- Collecting information directly from the target population. Through for example:

- Observation in both offline (e.g. public spaces like supermarkets) and online locations. For instance, social media or blog analysis could be a useful way to gain insights on the issues discussed in the community;

- Interviews (easily conducted through video calls);

- Surveys (easily conducted electronically using platforms like SurveyMonkey)

- Utilising other online tools to analyse activity online; for example analysing public search information on platforms like “Answer the public“.

2. Define: The idea for this stage is to define the problem. Our facilitator directed a session in which, both by utilising the insights gained from a variety of mixed methods described above, and by using a variety of structured methods to gain inputs from the workshop participants, they generated many problem statements. Again, this phase can be conducted online.

3. Ideate: This phase is about brainstorming possible ideas and communication approaches. It is important for the ideation phase to be conducted in a positive, non-critical atmosphere. This will help workshop participants to feel comfortable in putting any ideas forward. We did this in a workshop environment which can be done easily online using videoconferencing. You could also ideate by sending group emails asking for ideas, or through online platforms like Coggle.

The direction of the ideas should not be tightly specified at this phase – people need freedom to be creative. Some of the more obvious media channels that participants may decide to use in their COVID-19 communication strategies are videos, infographics, and webinars. To select or honing down of ideas to move forward, our participants voted on their favourite ideas, but we also sought input from experts.

4. Prototype and test: Through prototyping, ideas can be brought into life rapidly . They could range from anything from physical structures made of cardboard, through to post-it-notes on a wall, role plays, design mock-ups, or storyboards: Anything that communicates the idea well and enables critical reflection works. Our workshop created paper prototypes, and then conducted prototype presentations to gain constructive inputs. After reflection, they generated new and improved prototypes.

For COVID-19 this could involve, for example, designing a website layout with post-its and coloured pens on cardboard. After several testing cycles with potential users, the website could become a final website ready to be launched.

The information from this post has been extracted from the findings following the i-CONSENT project research. This and other information will be included in the project’s guidelines, that will be released very soon.